Sadness

For Alex.

It fills the ocean

Gray and fathomless.

It saturates the sky

Weighing down the cloud

Until it presses on the water.

It seeps into the soft edges of the world

Where something darker waits—

An intimation that the weather plans to settle in

Or turn wild and desperate.

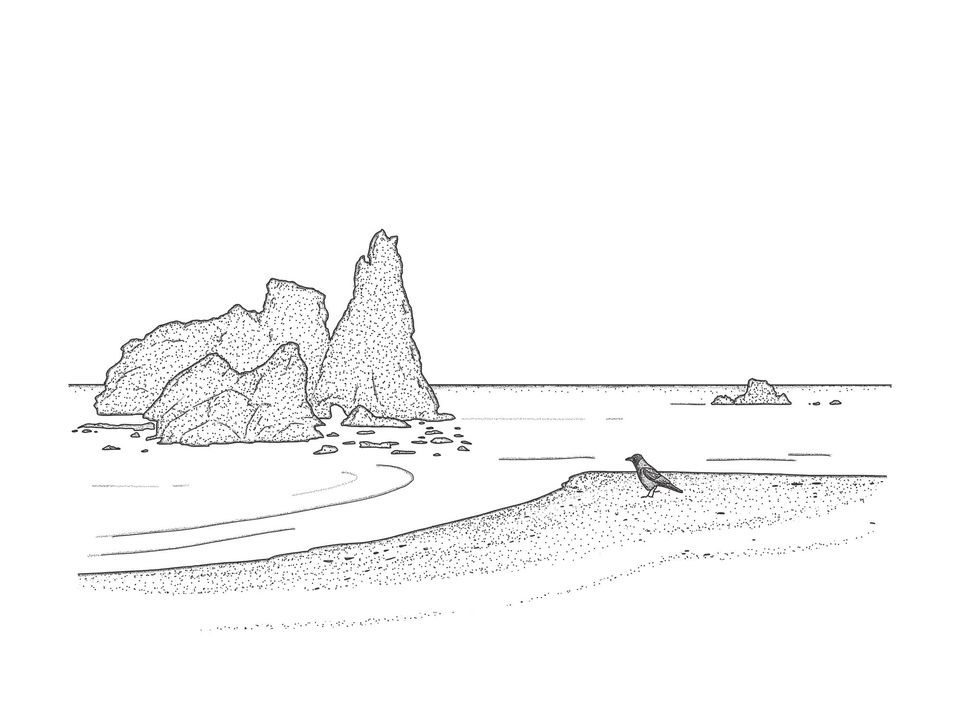

A beach, sloping to the ocean.

The rhythm of the sea against the shore.

A vantage point

From which I look across the water to the seam

Between the sea and sky

Barely visible.

There is something here

That was not here before.

A peacefulness. A hidden beauty.

A companion now, to my right.

We sit in silence

Looking out across the sea together.

The color has run from the sand into the water.

I turn to him and smile.

I suppose I should have been writing about gratitude this week, what with the Thanksgiving holiday in America. But sadness was here. So I wrote about that instead.

Sadness is always here, I think. Of all the emotions, it seems to me to occupy the world most fully and persistently. We seem wary of acknowledging its presence, as if naming it might give it greater power in our lives. I wonder whether the opposite might be true, that the world's false cheer can make us feel more apart and more alone in our sadness—more in its thrall.

How should we approach friends and loved ones when they are sad? We want to cheer them up. But when we fail to properly acknowledge what they are feeling, we can leave them feeling unseen and unheard. When we try to fix them, we can leave them feeling broken and helpless. Perhaps the very best thing we can do is be with others in their sadness—to be respectful of how they are feeling; to lend them our non-judgmental presence; to offer our unspoken belief and trust that they have the strength and courage to heal themselves.

Since childhood, "we are taught to ignore sadness," writes Katherine May in Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times, "to stuff it down into our satchels and pretend it isn't there."

As adults, we often have to learn to hear the clarity of its call. That is wintering. It is the active acceptance of sadness. It is the practice of allowing ourselves to feel it as a need. It is the courage to stare down the worst parts of our experience and to commit to healing them the best we can. Wintering is a moment of intuition, our true needs felt keenly as a knife.

The beach and sea came to me during a Gestalt therapy session. My sadness started as a feeling inside my chest. It then became the sea and sky, and quickly overwhelmed me. As I developed a perspective on my sadness from the beach, I was able to detach from it a little—to experience it as an observer of myself. It was then that I discovered the peace and beauty in it. Finally, my lovely therapist Alex asked me if he could join me on the beach. (It is totally cool to do this in Gestalt therapy, apparently.) I accepted his offer. He told me how beautiful it was. I laughed, surprised by the sudden sense of joy in me.

Unlike traditional psychotherapy, Gestalt therapy has no interest in analyzing why we feel the way we do. Its goal is to help us feel and experience ourselves more fully, in the present moment. As we gather up and reclaim the discarded, neglected and unloved parts of ourselves, we become more whole, dissolving internal blockages and removing resistance to the natural processes of change and growth that work through each of us, when we let them.

Gestalt therapy seems to bring the same philosophies to therapy that I try to bring to my coaching—that my clients are naturally creative, resourceful and whole; that in experiencing the wholeness of themselves, they connect more deeply with their own resourcefulness and growth; and that in teaching me about their lives, they learn more about themselves and find greater clarity. I am starting my two-year training as a therapist at the Gestalt Institute of the Rockies in February. I am super excited to see what I will learn!

Now that I have discovered my beach and sea, I have a beautiful place to go when I am feeling sad. I can even bring a friend so we can be sad together, in companionable solitude.

Rainer Rilke writes this in Letters to a Young Poet:

If a sadness rises up before you larger than any you have ever seen; if a restiveness, like light and cloud-shadows, passes over your hands and over all you do, you must think that something is happening with you, that life has not forgotten you, that it holds you in its hand; it will not let you fall. Why do you want to shut out of your life any agitation, any pain, any melancholy, since you really do not know what these states are working upon you?

Emily Dickinson's poem I measure every Grief I meet tries to take the measure of other people's sadnesses. It leaves me feeling the comfort and solace that I do not suffer alone.

I measure every Grief I meet

With narrow, probing, eyes –

I wonder if It weighs like Mine –

Or has an Easier size.

I wonder if They bore it long –

Or did it just begin –

I could not tell the Date of Mine –

It feels so old a pain –

I wonder if it hurts to live –

And if They have to try –

And whether – could They choose between –

It would not be – to die –

I note that Some – gone patient long –

At length, renew their smile –

An imitation of a Light

That has so little Oil –

I wonder if when Years have piled –

Some Thousands – on the Harm –

That hurt them early – such a lapse

Could give them any Balm –

Or would they go on aching still

Through Centuries of Nerve –

Enlightened to a larger Pain –

In Contrast with the Love –

The Grieved – are many – I am told –

There is the various Cause –

Death – is but one – and comes but once –

And only nails the eyes –

There's Grief of Want – and grief of Cold –

A sort they call "Despair" –

There's Banishment from native Eyes –

In sight of Native Air –

And though I may not guess the kind –

Correctly – yet to me

A piercing Comfort it affords

In passing Calvary –

To note the fashions – of the Cross –

And how they're mostly worn –

Still fascinated to presume

That Some – are like my own –

A little while back, the poet Ross Gay set himself the task of writing about what delights him, every day, for a year. The Book of Delights collects his daily labors, celebrating old music, pecans, family memories, and airplane rituals.

In a chapter that wonders about the meaning of joy, he writes this:

Is sorrow the true wild?

And if it is—and if we join them—your wild to mine—what's that?

For joining, too, is a kind of annihilation.

What if we joined our sorrows, I'm saying.

I'm saying: What if that is joy?

Each week I explore a life metaphor that has touched me in my coaching. Subscribe to get my scribblings every Sunday morning. You can also follow me on Medium, or on LinkedIn. Feel free to forward this to a friend, colleague, or loved one, or anyone you think might benefit from reading it.